Reverse engineering Human Resource Machine drawings

I recently played through the latest game from Tomorrow Corporation: Human Resource Machine.

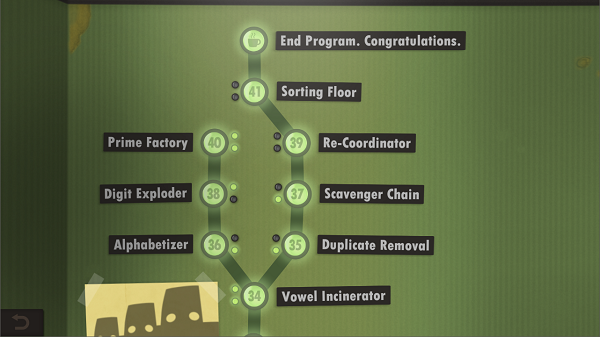

The game provides a friendly wrapper around a simplified kind of assembly language programming, and presents challenges in the form of what are essentially unit tests. Make the tests pass, and the level is complete.

The challenges start from the very basics and work up to some fairly complex programs, like prime factorization and sorting arbitrary-length sequences. It’s not a terribly hard game for someone with a bit of low-level programming experience – I completed all the levels in a single day, though I didn’t always meet the optional objectives (program length and runtime).

If you haven’t played the game, I recommend picking it up and giving it a shot.

The setup

There are two cute features in the game that piqued my interest:

1: Hand drawn comments

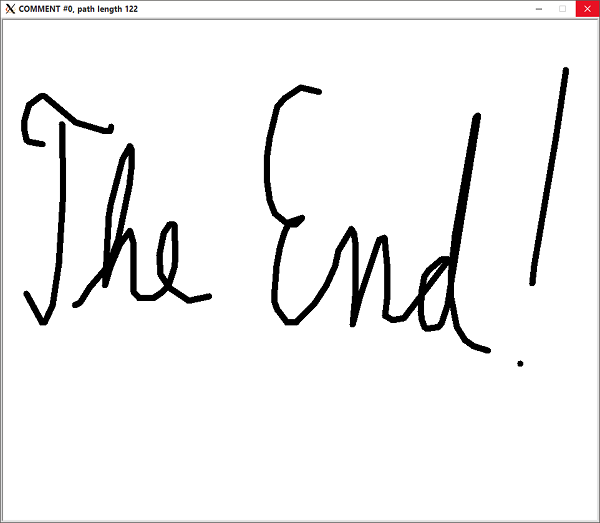

As the challenges get more complicated, the game provides a cute system for annotating your program in the form of a simple line drawing interface:

2: Textual program representation

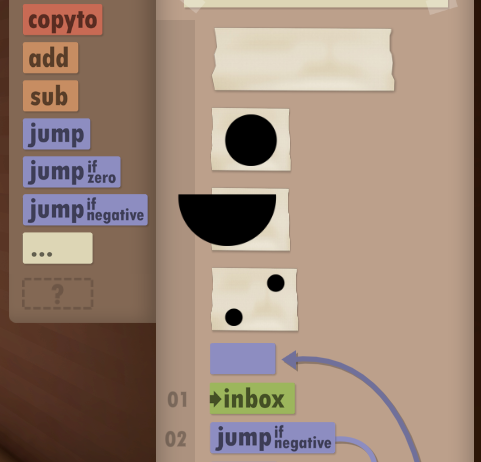

The in-game program editor is very graphical, with drag and drop editing, but programs can be copied and shared in a simple textual form. The game provides buttons for copying and pasting as a simple way to import and export programs.

Here’s an example:

-- HUMAN RESOURCE MACHINE PROGRAM --

COMMENT 0

a:

INBOX

JUMPN b

COMMENT 1

JUMP c

b:

COPYTO 0

SUB 0

SUB 0

c:

OUTBOX

JUMP a

DEFINE COMMENT 0

eJwrZ2BgaJQ6qsMr9lzXSMTbsES4z3ibUJX1ZWFFx2USPJ7zpL8H/JXuirOXFkxOkdyZ8UPQPjeB3z4X

qI3hgJq3obx6TEiiWlN+pOaSgkeGsjkgcXl1e42zuvYajkZ/VEH8OvW6UHEt62AdvQBvEP+Jxx9VM6db

Kn/sEzQV7SKsDtk+imiwc4+RdDybsMjzfSJIjVREZuyNiPlhNyLaXHaHm1nGhC/WNo/8o/o0/o8qU6K9

xt2kXKO6pAirxMS9tj6xqc76ManONsk8noHp88POZnTFgcyozjezlMk3ShGsL00D8WXy10ipNQvKgdiW

BYJye/NyjfbmzbaJrt5rCxKTnvxH1WLKZN+bkzNjQXy+HhC/VJFpTpckWP+qs9K3VqU6g/Wvnp4Oog2L

jVZW5xutbM7ZuZY9u2kLe/bz7SJFoocuFVUdvVTkfGZr4ckLR7Ov3Tyb8ePWhvStN0B6CurfL7OrUjpt

V8V7GcQ3q83dk9G0Yd/P9v69VzqbtlzpPLd0VrveFZCcxZQ1S25Odj4DYm+Z+nz77HnPt0fOb9pStuDc

0rIFdbN2zH99EST3fXXAVRC9as/JCyC66hzE7FEwCggBAIF9ryw;

DEFINE COMMENT 1

eJxTZWBguFSk6DijQNHxf26bi0mae4xLglnd0/iACfJJj+cGpk9fc6kod09yxaX9eg2X9ie0cuy80nlr

nfIEyemxk/Y2SU8+Whg7aWfGwwlnE172HgwX65zsu7+Vx/N+paKjYTHIXGenuLwVrkBrGMIKvctAdG+D

fS6INiz+MfVUad0szbLHcytqWOafr58/u7WZt49hFIyCUUA3AAAqNT89;

Notice the weird-looking blobs of text at the end. It’s pretty clear that those encode my beautiful hand drawn comments and labels in some way, but I had no idea how. My curiosity was piqued, so I started experimenting.

Reverse engineering

I started by creating a few labels to test simple cases: empty drawings, and single dot drawings at various known locations, like the center, corners, and sides of the drawing region.

[Note that the third drawing is actually a single dot in the top left corner, but the in-game renderer seems to have a bug for this corner case.]

The textual form of those labels is fairly informative:

DEFINE COMMENT 0

eJxjYBgFo2AUjGQAAAQEAAE;

DEFINE COMMENT 1

eJxjYmBgcCs3q2MYBaNgFIxIAADN+gF0;

DEFINE COMMENT 2

eJxjYmBg0GRYwTAKRsEoGJkAAE7pANQ;

DEFINE COMMENT 3

eJxjYWBg6M7k7QNSDLuqzyYwjIJRMApGFAAAwIMD9g;

Note how the labels all start with the same characters, and that the length of the data seems to roughly match the complexity of the drawing it corresponds to.

At this point, I was pretty sure that the text blobs in the program file were binary data in a base64 encoding. It’s a common way to represent binary data in text (see CSS image data URIs), and after seeing many instances of base64’d data one starts to get a sense of what the encoded result looks like.

So I wrote a quick script to base64 decode the blobs and save them to individual binary files. I had to do a bit of hackery to fix the padding for the decoder, but after a quick skim of the Wikipedia article on base64 I got things working:

import base64

def decode_hrm_drawing(text_blob):

# strip ; terminator

text_blob = text_blob[:-1]

# add base64 padding

if len(text_blob) % 4 != 0:

text_blob += '=' * (2 - (len(text_blob) % 2))

# decode base64

return base64.decodestring(text_blob)

blobs = [

'eJxjYBgFo2AUjGQAAAQEAAE;',

'eJxjYmBgcCs3q2MYBaNgFIxIAADN+gF0;',

'eJxjYmBg0GRYwTAKRsEoGJkAAE7pANQ;',

'eJxjYWBg6M7k7QNSDLuqzyYwjIJRMApGFAAAwIMD9g;'

]

for i, blob in enumerate(blobs, start=1):

with open('label%d.dat' % i, 'wb') as f:

f.write(decode_hrm_drawing(blob))Examining the resulting files with hexdump didn’t reveal any secrets, so I

turned to an old standby:

$ file *.dat

label1.dat: zlib compressed data

label2.dat: zlib compressed data

label3.dat: zlib compressed data

label4.dat: zlib compressed dataAha! That’s why the files looked like noise, they were compressed! Thankfully, that could be fixed with minimal changes to my script:

import base64

import zlib

def decode_hrm_drawing(text_blob):

text_blob = text_blob[:-1]

if len(text_blob) % 4 != 0:

text_blob += '=' * (2 - (len(text_blob) % 2))

# decode base64 -> decode zlib

return zlib.decompress(base64.decodestring(text_blob))The newly decompressed files weren’t identified by file, so it’s back to

hexdump:

$ hexdump -C label2.dat

00000000 02 00 00 00 46 77 36 7e 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |....Fw6~........|

00000010 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |................|

*

00000404Now, we’re getting somewhere. At this point I figured I should make a few more simple drawings, including some lines of various lengths. I haven’t included them in this post to keep things readable, but they were useful in testing my assumptions.

My first observation was that every file was the exact same length, regardless of the complexity of the source drawing:

$ wc -c *.dat

1028 label1.dat

1028 label2.dat

1028 label3.dat

1028 label4.dat

4112 totalCounting the number of non-zero bytes shows that the contents are fairly different, though (which explains the discrepancy in their compressed size):

$ tr -d '\0' <label1.dat | wc -c

0

$ tr -d '\0' <label2.dat | wc -c

5

$ tr -d '\0' <label3.dat | wc -c

3

$ tr -d '\0' <label4.dat | wc -c

9Most binary formats have some sort of header, so I looked at the first few bytes of each file and found what looked like an unsigned 32-bit integer which corresponds to the number of dots in the drawing:

ls *.dat | xargs -n1 hexdump -C -n8

00000000 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 |........|

00000008

00000000 02 00 00 00 46 77 36 7e |....Fw6~|

00000008

00000000 02 00 00 00 29 00 a8 00 |....)...|

00000008

00000000 04 00 00 00 8b 69 0d 8e |.....i..|

00000008[I should note that I’m not sure if the header integer is signed or not, but considering the apparent 1028 byte size limitation, it’s unlikely to matter.]

The first label is empty, so it’s header is zero. The next two are single dots, and their header numbers are both two. The last label has two dots, and a header number of four. Using my line segment test labels, I figured out that the header number must correspond to the total path length.

Armed with this knowledge, I worked out the format of the remaining data.

The non-zero data after the header in each file seemed to fit in header * 4

bytes. Since I knew that the data must be encoding a two-dimensional drawing,

and each 2-d coordinate requires two numbers, the most likely format seemed to

be pairs of short (16-bit) unsigned integers.

Working on that assumption, I updated my script once again:

import base64

import numpy as np

import zlib

def decode_hrm_drawing(text_blob):

text_blob = text_blob[:-1]

if len(text_blob) % 4 != 0:

text_blob += '=' * (2 - (len(text_blob) % 2))

binary_data = zlib.decompress(base64.decodestring(text_blob))

# Convert to numeric bytes with numpy

byte_data = np.fromstring(binary_data, dtype=np.uint8)

assert byte_data.shape == (1028,)

header, = byte_data[:4].view(np.uint32)

path = byte_data[4:4+4*header].view(np.uint16).reshape((-1,2))

return path

for i, blob in enumerate(blobs, start=1):

print 'label%d:' % i

print decode_hrm_drawing(blob)

print ''Running this on our examples yields:

label1:

[]

label2:

[[30534 32310]

[ 0 0]]

label3:

[[ 41 168]

[ 0 0]]

label4:

[[27019 36365]

[ 0 0]

[31674 24781]

[ 0 0]]

Hooray, it works! From this it’s pretty easy to see that the drawings are stored as sequences of (x, y) coordinates, with (0, 0) in the top left corner and (65536, 65536) in the bottom right corner.

[Note that 65536 = 216, the largest unsigned 16-bit integer value.]

The last observation is that disconnected line segments are separated by a (0, 0) coordinate. And that’s it!

The end result

With a complete understanding of the binary file format worked out, I expanded

my script to parse and render the drawings from a Human Resource Machine program

using Python’s

built-in turtle drawing library.

It’s not particularly fast, but it does make a cool animated effect.

You can check out the script here, and try it on your programs or the example programs in that repository.

-- HUMAN RESOURCE MACHINE PROGRAM --

DEFINE COMMENT 0

eJyrYmBgYOTfayvIOdvmC3uVtRn7ZzMzdm9DQc4ETWe+Wyr7+G+pVMrmGolrfTYL1Plsxq+7wQSohaFT

vM/4hfj8MF6xz9UlwoUT9/HXzVrEVzfrC/vJbpC8lGzhxBD5gAmZyqkdk7VFa9kNmvJvmVgHfzd97f7d

VNHR0vSe3SPDFa4bdDJjP2kLJotrObcH6pjVHTU4Wmhp+icrzGxJwVazFV1+lrx9dva8fcHOK7reuDq3

t3qY1T3x6K9o9Zie7u02PX2Ts2zOdcfc8qlOsxu93VI7rvjp9e8Of90DcsOs9ulK5+tDFA5V/FHNLm3S

EimKsPpekOr8vUAySKRILdqv5H2iXdX0dLPa6el6DUYpc6tK05IrZHM6yjhKeEpFa/1K2jr9SgImZJdu

mXy/sm7W1Nq6WXJtARM+djm3L+8TrVWeoFW6ZeqtzIvTZHP6pz8v6p/e1lk0bf7srJm8fSYLjxZ+WtiU

r7MkIW/F0oj6FUtPdncvkZz+aHnMzK1rrGckHNhQybl3Q2XF9oj6uVv3NjVsaetU3HJtSsOWmJlztx6c

s2vb47lvdh+ck7EXGK77Cyf+O8Oh//C0lsHPQ/a5tQcj6msP8vZtP3xwTu7xrsXKp98vK7potBLk5577

f9aD6L1PFNuqn4rWKr6PsJr62V2cYRSMAhwAAEo81oA;